In the Art of War, Sun Tzu famously said you should know your enemy. My enemy is pollen. Every spring, just as I get excited about warm weather, the enemy attacks. I've got such bad allergies that when I went to an allergy clinic to get tested, the doctor called in all the nurses and said, "Now THIS is an allergy patient." He was more excited about it than I was.

As I've battled pollen the last few months (the ragweed is preparing its attack now), I've decided to take Sun Tzu's advice and learn something about my annual foe. And what I've discovered is that pollen isn't entirely my enemy. In fact, it's pretty amazing stuff. Without it, there would be no flowers. There would be no bees, no honey, and no hummingbirds. There would be none of the crops that feed the world--no wheat, no rice, no corn, no apples, bananas, or pears. Worst of all, there would be no coffee.

The reason none of these things would exist is that pollen is how most of the world's plants reproduce. Any plant that produces seeds--including evergreens and flowering plants--uses pollen to reproduce sexually. Since plants can't step out in search of a mate, they have to let their pollen do the traveling. That's all a pollen grain is: a tiny, tough vehicle for plant sperm cells.

Some plants, like conifers, are lavish with their pollen. They produce huge amounts of it, and scatter it to the four winds. Many flowering plants, though, take a more targeted approach. They recruit animals to carry pollen for them, delivering it directly to other members of their species. That lets them produce much less pollen, but it requires a sophisticated animal-attracting device: a flower.

Flowers evolved to entice bees, birds, bats, flies, and other animals to visit them, pick up some pollen, and carry it to another plant (though some flowers have "regressed" back to wind pollination). Their bright colors and fragrant scents exist in order to attract pollinators, and nectar is the reward flowers offer in exchange for pollination services.

Bees and many other animals have co-evolved with flowers, and now specialize in pollinating them. Most bees, for example, live entirely on nectar and pollen, and they're perfectly adapted to that lifestyle, with long tongues for drinking nectar, hairy bodies for trapping pollen, and even "pollen baskets" on their legs. Hummingbirds are also adapted to live on nectar, with long beaks and tongues, and the ability to hover in place. Hummingbirds are a dramatic example of how much pollen can shape the world. If birds are the only dinosaurs that never went extinct (as most scientists believe), then hummingbirds are what happens when nature tries to turn a dinosaur into a bee. And it wouldn't have done such a weird and wonderful thing if not for pollen.

Flowers often reflect the pollinators they try to attract. For example, most flowers that attract birds are some shade of red, and have little scent, because most birds have little sense of smell. Flowers pollinated by flies, on the other hand, can smell pretty gross--the corpse flower gets its name from its odor, not its appearance. Large, pale, night-opening flowers are usually pollinated by night-flyers like moths and bats. The yucca plants on the hillsides around Denver can't reproduce without symbiotic moths, and their relative, the agave (source of tequila) is pollinated by bats. The traveler's palm of Madagascar has tough flowers that can't be opened by insects, birds, or bats. It's pollinated by lemurs.

People often blame flowers for their allergies, but that's usually a false accusation, because plants with conspicuous flowers are animal-pollinated, not wind-pollinated. That means not much of their pollen gets into our eyes and noses. The real culprits are the plants that wantonly scatter their pollen into the air, like grasses, ragweed, and many trees--both deciduous and evergreen. Conifers, which scatter a lot of pollen, don't even have flowers. Grasses and deciduous trees do, but wind-pollinated flowers are usually small, drab, and hard to recognize as flowers. The fact that most allergies are caused by wind-pollinated plants is the reason honey probably doesn't help with allergies, even if the idea seems clever. Bees don't make honey out of the plants that cause allergies.

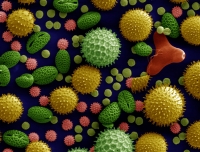

So, are the wind-pollinated plants my real enemies? No, not really. After all, civilization as we know it couldn't exist without wind-pollinated crops like rice, corn, wheat, and oats, or trees like oak, hickory, ash, spruce, fir, and pine. Can you imagine Colorado with no evergreens in the mountains or grass on the plains? Besides, wind-borne pollen has played a crucial role in human knowledge. As you can see in the first image above, different plants produce very different and distinctive pollen grains. That means all that pollen in the air leaves a record that scientists can use to learn an amazing amount of information. At Rocky Mountain Park, they've used ancient pollen in the soil to reconstruct how plant life and human settlements have changed with the climate as the glaciers receded. At Florissant Fossil Beds, fossil pollen has been crucial in reconstructing an ecosystem from 34 million years ago. Archaeologists use pollen to learn what ancient people ate. Forensic scientists use pollen to solve crimes. All around the world, scientists are digging into layers of ice, soil, and rock to read the many tales pollen can tell.

All things considered, then, pollen isn't really my enemy. But it's not always my friend, either, and sometimes I have to fight it. And Sun Tzu was right: knowing your opponent is crucial. So where can you find reliable information about dealing with pollen allergies? You ask a reference librarian, of course! DPL's research page on Health has links to several reliable databases. One good resource there is Medline Plus, which is a portal to medical information compiled by the National Library of Medicine. You can search there for "seasonal allergies," or if you want to get more technical, "allergic rhinitis." Health and Wellness Resource Center is also a good resource. The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology is the professional society for allergists. They have a good educational website, and they run the National Allergy Bureau, which is the country's main network of stations that measure pollen counts.

All this information may not cure allergies, but I've found that it helps me deal with them, and to appreciate all the things pollen is good for. I still sneeze this time of year, but now I sneeze more philosophically.

Questions? Ask Reference Services or call 720.865.1363 today!

__________________________________________________________________

Further Reading and Resources

Library Books

The Private Life of Plants: A Natural History of Plant Behavior / David Attenborough

Seeing Trees : Discover the Extraordinary Secrets of Everyday Trees / Nancy Hugo

The Fossils of Florissant / Herbert Meyer

Library Database Articles (Log in with your library card)

Ensminger, Peter A. "Pollination." The Gale Encyclopedia of Science

Anderson, Bruce. "Coevolution." Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia: Evolution

"Pollen Analysis." The Gale Encyclopedia of Science

"Allergic Rhinitis." Medline Plus

Websites

The Hidden Beauty of Pollination. Louie Schwartzberg: This TED talk features a beautiful video about pollination.

Hay Fever/Rhinitis: American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology